A fictional account of William Beebe and Otis Barton’s famous historical bathysphere dives off Bermuda in the 1930s

By ALEXANDRA STEWART | September 15, 2014

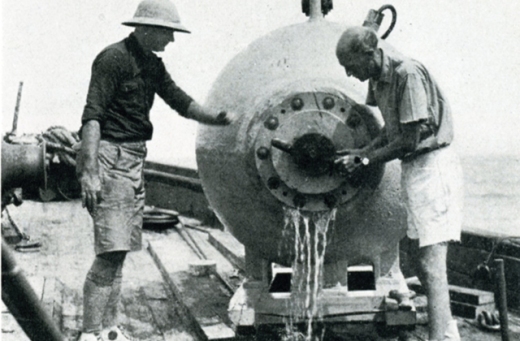

It wasn’t an expedition for the claustrophobic. Two and a quarter tons of steel dangled from a cable less than an inch thick. The four-foot-wide interior had to accommodate not only the two men, but bulky technical equipment, oxygen tanks, photographic apparatus, and lights and trays of chemicals to soak up carbon dioxide. At 3,000 feet below the surface, the water pressure exerted per square inch exceeds 1,000 pounds. It was an enormous undertaking, not just dangerous but a truly original attempt to explore a completely unknown part of the planet.

The bathysphere was engineer Otis Barton’s brainchild, based on his own designs and built at his own expense. Barton approached naturalist and explorer William Beebe, after reading of his deep-sea diving ambitions, hoping to join forces. Beebe was already something of a celebrity scientist, having published a number of successful and popular books, as well as having gone through a messy public divorce. Barton didn’t have the connections to fully fund his own ambitious diving plans. He knew his as yet unnamed sphere was better able to withstand the immense pressure of the ocean depths than Beebe’s reinforced cylindrical diving tank, and Beebe evidently realised Barton was on to something. An uneasy partnership was born as they worked together to organise financial and public support for their project – a difficult prospect in 1929 in the wake of the Wall Street Crash.

Bermuda was an ideal base for their expeditions; the shallow waters close to shore and the sudden drop of the seamount into deep water gave them two very different ecosystems from which to gather data. A scientific team assembled labs on Nonsuch Island to examine specimens caught in trawling nets. Among them was Beebe’s assistant John Tee-Van, illustrator Else Bostelmann, and Gloria Hollister, an ichthyologist who also manned the telephone, the lifeline between the men in the bathysphere and the surface.

From 1930 to 1934 Barton and Beebe set consecutive depth records in the bathysphere and on August 15, 1934, they descended to 3,028 feet, setting a record that would stand until 1949. Hollister would also break barriers, eventually descending beyond the 410 feet mentioned in this story to over 1,000 feet – a depth record set by a woman which would remain unbroken for 30 years. Records aside, these individuals were pioneers in the truest sense of the word, seeking to illuminate the unknown and broaden our understanding of the world.

Herewith, a fictionalised account of the August 15, 1934, descent in the bathysphere, when Barton and Beebe set the world record. Their observations of the environment they discovered were relayed to Gloria Hollister at the surface via telephone.

She begins with a curved black line.

Beebe’s voice surfaces every now and then in her ears, the phantom weight of headphones long since removed. Miss Hollister. She tries to focus on the thin arc across the paper. The unidentified fish from this morning is still precise in her mind but she feels the edges of it could bleed together at any moment. She widens the line at the base. She adds a fin. Gloria, what do you see?

At her desk she sees her fingers as they were on the glass of the bathysphere, dark against the shifting green light of the water.

Yesterday she sat sweating in the shade of the barge, watching the crew bolt the hatch down once Beebe and Barton had twisted their long bodies inside. She hated the weight of the moment before the bathysphere was winched out over the water; she hated the pneumatic thud of the bolts hitting home. The thought of being sealed inside caused her to feel something between anxiety and envy. She worried whenever they went down, imagining a crack like a spider’s web in the fused quartz windows, the immense bolts shaking loose. Beebe’s cacophonous profanity whenever the bathysphere swayed in the air didn’t do much to calm her.

But then his voice would rise in her ears, sharp gasps and feverish exclamations all coming at a barrage. She had to concentrate, make sure they kept up a constant dialogue; a silence of even five seconds and she’d have to signal the crew to winch them up. The incessant, giddy buzz of Beebe’s narration replaced her own in her head. A lovely, bright, solid pale blue light at the glass. Probably – oh, I don’t know. She fired questions at him, kept him focused when he became vague and for a moment did not recognize the feminine inflection of her voice. How many? How small is it?

As small as an American penny.

At nine hundred feet Barton cut in, measured and clinical. Oxygen nineteen-hundred pounds. Humidity fifty-five percent. Temperature eighty-five. Hose all right. Door all right. Barometer seventy-six and one half. He paused before adding, Only dead men have sunk this far.

She pictured the two men, cramped and curled around oxygen tanks, photography equipment and her disembodied voice, the claustrophobic intimacy of the luminous dark.

Luminous dark. Beebe’s phrasing in her head again. It frustrated her sometimes; his romantic descriptions made it difficult to contain, to stop the shape of the fish from exploding in every direction at once.

You know what a contradiction that is, don’t you?

There is no other way to explain it, he told her, not for the first time.

It is impossible.

Not if you’ve seen it.

Twilight rising, Barton’s voice filled her headphones unexpectedly, then silence. Five seconds passed.

Gent-

Oxygen at thirteen-hundred, Barton interrupted. Temperature at eighty six. Where are we?

At fifteen-hundred feet, she said.

On deck she was baking in the August heat, aching for a breeze to pick up. The shadows had receded and the whirring pitch of the winch, Beebe’s torrential observations had started a dull thumping in her temples. She glanced up every now and then from her notebook and squinted out over the deck. She watched the crew inspecting the cables; she saw how their mouths moved and their arms gestured but she couldn’t make any sense of it. She was disoriented by the closeness of the men in the bathysphere and the sprawling openness of the barge’s wide deck, and beyond that the immensity of the sea. She was in some nowhere place between the two, linking them but somehow not connected to either.

An anglerfish, quick, by the window. I only caught a glimpse. There’s a pair of leptocephali – large, twisting like willow leaves…

Mr. Beebe, –

Both of them about eight inches long. More of them now, sweeping along in a line.

Mr. Beebe, the anglerfish. What of its size? Colour?

Black. Medium. Wide-mouthed.

Luminescent?

No tentacle lights. No lights on the body. Its teeth were glowing. Faintly. A pale lemon-yellow.

She had seen his sketches of the unnamable creatures and at first thought the dark had turned his mind. What else was she to think when he presented her with those loose-leaf monsters? A detail of teeth, an outline of some unknown twisting body; here a perversion of a fish, all maw and tentacles. Apocalyptic visions sketched by a mad, desert prophet.

It wasn’t until the nets had dredged up a few flesh and blood specimens that she started to take his drawings seriously. The fish were damaged and crumpled from the sudden depressurization, and Beebe claimed they didn’t hold a candle to the living ones he had seen, but for her they were a revelation.

Barton look! Miss Hollister, something big. A cetacean probably. It moved all wrong for a squid. Barton missed it.

You’re at twenty-four hundred now.

Our friend is deep. Beam off.

It was noon when they set the record. She held up the telephone so they could hear the cheers and whistles coming from the barge half a mile away at the surface. Beebe, in the middle of describing a shrimp explode, sounded nonchalant, almost annoyed at the interruption.

How far down are we?

Three thousand and twenty eight. No one has ever seen what you are seeing now.

Utter blackness and a spray of bioluminescent constellations.

You may as well be in space.

I hope it has as much life as I’m seeing now. The shrimp left no trace of colour. I think we’re ready to come up.

The fish has evaded her. She cannot get the shape of the fins to match the figure in her mind’s eye. She scrunches the grey smudged paper between her hands and begins again.

Today is her birthday; thirty years old and she, still riding on the excitement of yesterday, would have forgotten it entirely if it wasn’t for Beebe gathering the crew around him on the deck that morning. They were all a little slow and unsteady after a night of heavy celebrations and she wasn’t focused on Beebe’s speech at all until he took her hand.

What do you think? Is this an appropriate way to celebrate such a momentous occasion?

Last night wasn’t enough for you?

The crew chuckled as Beebe beckoned to the round opening of the bathysphere.

Such things you’ll miss if you don’t listen. Happy Birthday, Gloria.

She dove inside gracelessly, hangover gone and settled herself on the thin cushions by the window. The air was thick and hot though the curved metal at her back was cold enough to prompt a shiver. Barton maneuvered in an inch at a time, pushing aside canisters and equipment until he made a space to seat himself. He braced his feet on the opposite side, nearly level with her ears. She wasn’t short by any means, but she was small enough to be quite comfortable and she could’t help but give Barton a smug little smile.

I was built for this. You should have let me down in the beginning.

Barton fished a wad of cotton from his pocket and passed it to her.

Pack that in your ears. It’s about to get loud.

Despite having grimaced in sympathy for Barton and Beebe all these weeks when watching the crew seal the door in place, she was still unprepared for the bone-shattering reverberations that followed. Her teeth felt loose and her head unhinged. In an instant, her old fears came back to her. How could the quartz withstand such pressure? She felt sure the windows would break; the water would seep in and drown them. After an eternity, silence fell and Barton adjusted the valves on the oxygen tanks, his smile echoing hers earlier.

A small price to pay Miss Hollister, I promise you. Beebe? Take us down.

Her apprehensions dissipated as soon as they made splashdown. The potential disasters that seemed all too likely on previous dives were carried to the surface in a cavalcade of foam and bubbles. The waters cleared and the ocean unfurled itself before her.

The sunlight streamed down in golden-green shafts that fell like curtains and she felt as though she were traversing an infinite cathedral. The incandescent motes of micro-organisms suspended in the water like dust in the air; the delicate clouds of jellyfish and long strings of siphonophores –

It’s like a garden, flowers everywhere.

You’re mixing your metaphors. First I think you’ve found God, now you think of petunias?

Are they not the same thing? That prompted a laugh from him that lasted a hundred feet.

At this depth, red was a memory; fish she should have recognized were phantom copies of themselves. Looking over at Barton, she saw only a featureless mass, a blurred patch of grey and black that grew dimmer with every passing second.

At three-hundred feet the dark poured into the bathysphere like oil, with a sudden, unexpected swiftness. She and Barton breathed it, they spoke it in a blue-violet whisper; she could even hear it under the hiss of the oxygen canister as a low, rumbling growl. With the beam off she could make out the shape of fish like plumes of smoke against a night sky.

You’ve lingered there for nearly ten minutes now. Beebe sounded anxious.

Just wait, she pleaded. Beam on.

It was then she saw it, the fish that had been tormenting her all day with its impossible dimensions. It slithered into the light only for an instant, pale grey underbelly exposed as it twisted up, chasing something imperceptible to her eyes. It turned, glided past the window with its mouth open, and in it she discovered a veritable firework display; long teeth, faintly lavender, and a row of blinking indigo lights leading back towards the gullet.

Miss Hollister, I’m going to have to insist. With a final flick of its elastic tail, the fish slid out of sight.

You’ve set a record, Barton told her, as if that were enough. The first woman to have traveled so deep.

At four hundred and ten feet it was nearly impossible for her eyes to adjust to the darkness, but she knew, hovering just below them, was oblivion, teeming with Beebe’s luminescent monsters. Looking straight down she could see it, a barely discernable line dividing the primal brilliance of the blue-black from a deeper violet. What did records matter when she was perched on the edge of so alien a border?

Miss Hollister, Beebe’s voice came sliding down the telephone wire. Do you still think me mad?

At the surface she felt dizzy, affronted with the array of colours and the brightness of the day. The crew crowded around her, passing on their congratulations but she barely heard them. Their voices passed through her and merged with the rising heat coming off the hot, polished metal of the barge.

Tell me, Gloria – what do you see? She sees in Orion’s Belt a school of flashing shrimp. She sees colour in her speech, tongue painting her words indigo. At her desk she sees her fingers as they were on the glass of the bathysphere, dark against the shifting green light of the water and she feels some fundamental part of her has yet to resurface.

She recalls the fish. It turns towards her, mouth agape and glowing, and before she is swallowed, she takes up her pencil and begins with a curved black line.